CAT OF THE DAY 078: THE THIRD MAN (1949)

CAT OF THE DAY 078: THE THIRD MAN (1949)

Or: THE THIRD CAT. We all know dogs are shameless brown-nosers who long ago sold out their dignity to perform demeaning tricks for a mess of Chum. But cats, due to their independent nature and all-round contrariness, are notoriously hard to train. They can sometimes be hoodwinked by smearings of tuna, but mostly they can’t be bothered to do what humans want them to.

It’s little wonder film-makers so often use stand-ins – one cat whose speciality is walking in medium-shot, for example, another cat which may enjoy playing with a ball of wool, and yet another which is an expert at close-up purring without attempting to play pat-a-cake with the camera operator. So long as the different cats look more or less alike, no-one will notice.

Even so, it takes only a cursory glance at The Third Man to ascertain that no-one has made the slightest effort to match up the kittens. The pivotal feline contribution here is a classic CATGUFFIN: it’s the kitten’s mewing that first alerts Holly Martins to the presence of the figure he will presently recognise as Harry Lime, the friend he thought dead.

Director Carol Reed builds up to this famous movie moment with careful editing and judicious use of zither music. Just prior to the scene, Martins has learnt the truth about his friend’s penicillin racket and has been out drowning his sorrows; he lurches drunkenly up to the flat of Lime’s girlfriend, Anna Schmidt, with an armful of flowers. It’s here that we first meet the kitten; Martins tries to get it to play with a piece of string, but it yawns, turns its back on him and exits through the open window.

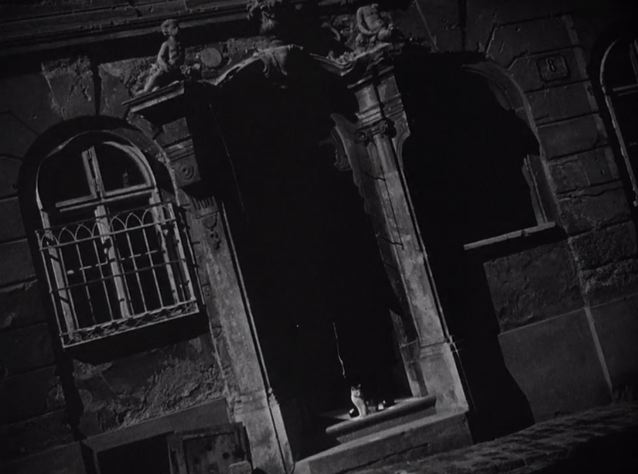

“Not very sociable, is he?” says Martins, to which Schmidt replies, “No, he only likes Harry.” They talk in a desultory way about what they have learnt from Major Calloway, and the camera takes off through the window and out into the street, where a man (too far away for us to identify) seems suddenly to realise he’s being filmed, and ducks into one of the doorways opposite.

CAT

The first peculiarity here is that the kitten now appears around the corner from the left; cat lovers may well start wondering exactly how the little kitty got down from the window-box so quickly (Schmidt’s absurdly grand apartment is on the first or second floor, at least) and why it is now appearing from the opposite side of the street. The simple answer, of course, is that it’s an entirely different kitten.

The Second Cat runs along the street towards the doorway where Lime is hiding. But wait, the kitten which we now see rubbing lovingly against his brogues is a Third Cat! We get a good look at its face as it gazes adoringly up at the shoes’ owner.

When I shared this discovery on Facebook, Nicholas Royle demanded the kitten continuity person be fired. Barbara Roden wrote, “Fire the balloon continuity person as well; the balloons the old man is selling have designs on them, but the balloon purchased by Paine – which has a design on it initially – is a plain one in a subsequent shots.”

So obviously, continuity was not a high priority on this production; maybe they were probably too busy making a masterpiece to care. Besides, one of the themes of the film is perception, and how things look different depending on the viewpoint, and as Neil Williams observed of the multiple kittens, “Given the number of shots of Harry Lime that aren’t Orson Welles it might just be a clever in-joke.”

Indeed, The Third Man is full of stand-ins for Orson Welles, who was leading a nomadic life when he accepted the role. (Read Rob White’s The Third Man, in the BFI Film Classics series, for some excellent in-depth analysis and behind-the-scenes information.) No sooner had the actor signed on to do the film (he later regretted his decision to accept £100,000 for a few days’ work instead of 20% of the film’s profits) than he disappeared, was finally tracked down to Italy and turned up two weeks late for shooting; he refused to film in the sewers, and numerous body doubles had to be used in his absences.

Arguably, his elusiveness only helped the film, as it turns Harry Lime into an even more mysterious and mythical figure; you’re never quite sure whether that shadowy figure is him or, say, a passing balloon salesman. But that’s not all. Let us take a closer look at the kitten playing with the shoelace:

Donner und Blitzen! Could this be… a Fourth Cat? The muzzle certainly looks different, though this sentence is written by someone who for fifteen years shared her life with a tabby-and-white, and is thus probably more sensitive to variations in the markings of this type of moggy.

But a simple yet classic cat-related moment has somehow now escalated into a case of MULTICAT which eerily echoes the central mystery that kicks off the film: who was the third man helping to carry Harry Lime’s body across the street after his accident? Who are the second, third and fourth cats? How many of them belong to Anna Schmidt? Are they related? Do they all like Harry Lime? And isn’t it just typical of cats, that they should want to cuddle up to this man whose cynical, mercenary actions have destroyed lives and left small children crippled?

Of course, the kitten is also a classic CATAPHOR. Throughout The Third Man, we are repeatedly led to believe that Anna Schmidt is helplessly, hopelessly, unequivocally in love with Harry Lime, yet Alida Valli and Orson Welles have no scenes together until near the end, when he walks into the trap laid for him by Martins and Calloway at the Café Marc Aurel, and she cries, “Harry get away! The police are outside! Quick!”

Even now they are not sharing the frame, but she shows no hesitation in trying to help him, even when he pulls a gun. All through the film, we have been required to take this love on trust, with no physical contact, nor even dialogue between the two characters. Indeed, for much of the narrative she, like Holly Martins, supposes him dead. How then to convince an audience of her unwavering devotion?

The answer, of course, is her cat. The kitten is her familiar, the symbol of her love and fidelity (note how her pussy refuses to play with Holly Martins) which she subconsciously sends out into the night to nuzzle the feet of her lover, play with his shoelace (paging Doctor Freud!) and gaze up at him in wide-eyed adoration. Throughout her conversation with Martins in that scene, her cat is otherwise engaged. That there is, in reality, more than one kitten involved, only emphasises the singularity of her purpose; there may be a multiplicity of cats, but they are all performing in concert, acting out her wishes and desires, leading us to the man she loves.

Related articles

- See “Les Miz” Put On by Kittens (catster.com)

- The Fanglish Dictionary of Essential Cat Slang (catster.com)

- Feline Detour Tunnels – The Cat Transit System Reroutes Kittens Above Ground (TrendHunter.com) (trendhunter.com)